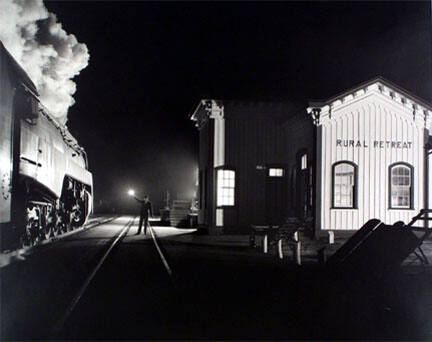

NW 1635-Birmingham Special, Rural Retreat, Virginia

Maker

Link, O. Winston

American, 1914-2001

Date1957

MediumGelatin silver print

Dimensionsoverall: 16 in x 20 in

Credit LineGift of James J. Brennan, Brennan Steel

Object number1986:174

About the ArtistIn the early 1950s, O. Winston Link read in a magazine for train buffs that diesels would soon replace steam locomotives. Hearing that Norfolk & Western Railway planned to phase out steam engines, Link proposed taking pictures along the line’s 2,500 miles of track through Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina. He took the first picture of the project in January 1955, and had created some 2,400 images documenting America’s remaining steam-powered trains and the communities they were a part of by time the trains ceased operation five years later. (When he began, all trains on the line were steam-powered, the last of which ran in May 1960, and the line itself would end in 1963.) From 1955 to 1960, Link made at least 17 trips from New York, concentrating on the 238-mile Shenandoah Valley Line from Hagerstown, Maryland to Roanoke, Virginia, a line dating back to 1870.At first, Link concentrated on what he called “hardware shots,” shots of stationary locomotives that were mostly a record of their physical construction, but he soon transitioned to the features for which his photographs are famous: trains moving at full steam, contextualized by regional landscape and trackside towns, most often at night. Nothing about making these pictures was easy. It was hard to count on train speed and he could never be sure what the wind would do with the steam, but Link claimed it was the sun that was “too hard to control.” Photographing at night restored a certain amount of control to the photographer, but it came at the price of intense technical demands. Most exposures are 1/200 or 1/100 of a second, shot usually with a 4x5 Graphic View Camera and sometimes as many as three cameras synchronized. The synchronized flash system necessary to freeze a train on film was custom built by Link and included up to 60 flashbulbs per picture. One broken connection and the entire system would fail, and it was prohibitively expensive to do any test runs.

Link did the project completely at his own expense. When Norfolk & Western realized the magnitude of his project, however, they did provide him with a key to the phone boxes along the tracks. This communication allowed Link to not only check on train times, but sometimes ask trains to change speed, clean the engine to produce whiter steam, and even reverse and pass again. Link meticulously planned both composition and narrative in his photographs, and just setting up a picture could take from several hours to two full days. It took enormous collective effort to make these pictures, and they reflect Link’s many friendships with train personnel and members of the communities in which he photographed. It is important to remember that Link’s pictures do not record simply steam trains but the trackside rural America that would disappear with them. Indeed, it seems his fascination with steam trains was equally matched by his affection for the people and small towns connected to them.

Ogle Winston Link was born in Brooklyn, New York on December 16, 1914. His father introduced him to photography, and by the age of 15, he was already taking pictures of trains. He never formally studied photography, graduating from Brooklyn’s Polytechnic Institute in 1937 trained to be a civil engineer, but a shortage of engineering jobs and a series of coincidences led him to a career as a commercial photographer. In 1942, he took a job with Columbia University’s Division of War Research, where he began to study night photography. At war’s end, he established his own studio in Manhattan, funding his personal projects from newspaper, fashion, and advertising assignments. It was not until the early 1980s that curators began to discover him. Indeed, long before his pictures garnered much attention, he was known instead for the sound recordings of steam-engine noises he made at the same time and collected into a series of six long-playing records. Since 1983, however, his photographs have been exhibited at Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago; Robert Klein Gallery, Boston; A Gallery for Fine Photography, New Orleans; Robert Mann Gallery, New York; The Light Factory, Charlotte, North Carolina; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Jan Kesner Gallery, Los Angeles; Fay Gold Gallery, Atlanta; Light Impressions’ Spectrum Gallery; Rochester, New York. His work is included in such collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Victoria and Albert, London; and the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. Link died on January 30, 2001. The O. Winston Link Museum, housed in a 1905 passenger station for the Norfolk & Western Railway, opened in Roanoke, Virginia in January 2004.