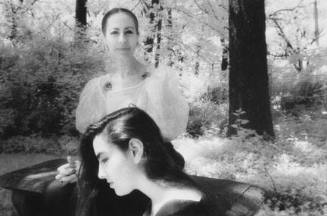

Experiment 27

Maker

Stieglitz, Alfred

American, 1864-1946

Maker

White, Clarence

American, 1871-1925

Date1909

Dimensionspaper: 11 3/4 in x 8 1/4 in

Credit LineExtended loan of the Baum Family Collection

Object numberEL2003:79

Collections

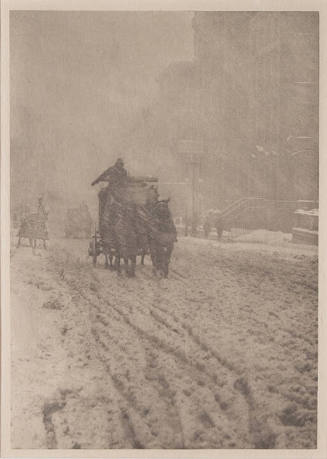

About the ArtistAlfred Stieglitz’s photograph The Asphalt Paver, NY (1892/1913) is a paradigm of pictorial photography. The main figure, the asphalt pavior, is generic, unidentifiable and absorbed in activity as he bends over his materials. He seems small and indistinct within the winter landscape of barren trees, and the distant trestle that frames the scene suggests the triviality of his labors compared with the scope of industry. This sort of genre scene was typical of pictorialism, but such pictures were not deemed successful unless they also conveyed the atmosphere and mood of the scene. In The Asphalt Paver, atmosphere is suggested by the white clouds of steam billowing from the small furnace. In another of Stieglitz’s photographs, Portrait - S.R. (1904) 1913, the ambiance of the portrait is evoked by a soft focus and the action of the subject caught as a blur in the photographic image. The atmosphere of these two images differs drastically from that of photographs produced by Stieglitz just a few years later. One of Stieglitz’s hallmark photographs, The Steerage (1915), produces a very different effect. The subjects are in sharp focus and the composition is inclined toward geometric elements of the scene instead of soft, picturesque ideals.- 19th and early 20th century

The distinction retrospectively drawn between nineteenth century and twentieth century photography frequently exaggerates the swiftness with which pictorialism was abandoned in favor of modern styles thought to be better suited to subjects of contemporary urban life. In the years leading up to the turn of the century, highly stylized and symbolist-oriented imagery of the late nineteenth century began to give way to a new kind of art photography that made no attempt to conceal its relation to earthly reality or to the apparatus of the camera. The career of Alfred Stieglitz is a useful guide to the complexities of this transition because it not only bridged the change in style, but also helped to establish the viability of new technical, formal, and expressive pathways in photography. Stieglitz was originally a leading figure in the promotion of the idea that photography harbored the same aesthetic potential as painting, and he fostered the progress of artistic photography in this direction by showcasing the work of young photographers who challenged the dominant conception of the medium. Instead of showcasing the use of photography as a tool for documenting or depicting the details of nature, these young photographers attempted to show, primarily through imitation of painterly styles, that photography could attain status as an art form. The artists exhibited by Stieglitz in the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession beginning in 1908 (known simply as 291, the address of the building that housed the exhibition spaces) included F. Holland Day, Clarence White, Gertrude Käsebier, Eduard Steichen, and Frank Eugene. Stieglitz’s contribution to the reformulation of aesthetic photography, however, went beyond his curatorial work; as a writer, editor, gallery owner, and publisher, Stieglitz virtually lived the ideal of fine art photography.

Alfred Stieglitz was born in New York in 1864. After studying engineering and photochemistry in Berlin for eight years, Stieglitz moved back to New York in 1890. Because he considered himself to be a true amateur, he was not as interested in making a name for himself as he was in making a name for art photography. Consequently, Stieglitz pursued editorial roles at several American photographic journals including the American Amateur Photographer, where he was the editor in chief from 1889 to 1897, and Camera Notes, the publication of the Camera Club of New York, where he assumed an editorial position in 1897. In 1902 after the dissolution of Camera Notes, Stieglitz founded Camera Work, the publication that would be the public image of the Photo-Secessionists as well as the first outlet for new European art in the U.S. Informed by his 1890 partnership in the Photochrome Engraving Company, Stieglitz had a critical understanding of the various printing techniques used to reproduce photographs. He chose the techniques, which included gum bichromate prints and photogravures, and supervised the making of each image published in Camera Work. Through this endeavor, Stieglitz became the first to outline a standardized mode of publishing art photographs and exhibiting them in a gallery setting.