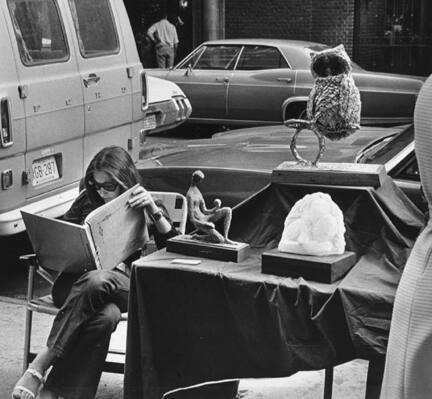

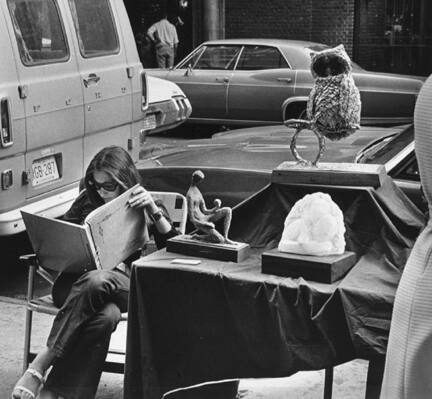

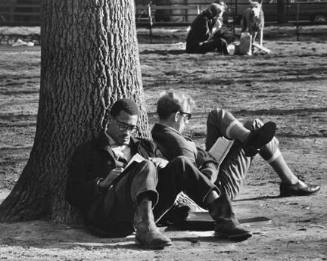

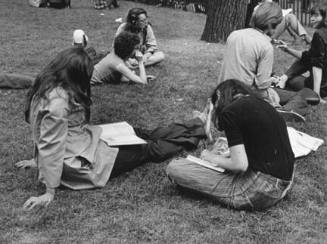

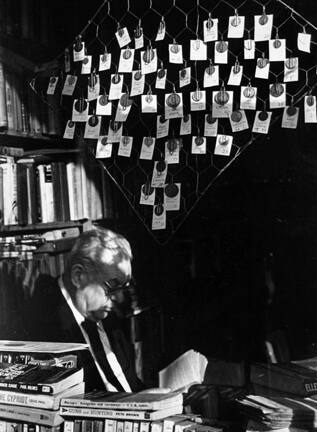

Washington Square, New York (reading at the art fair)

Maker

Kertész, André

Hungarian, 1894-1985

Date1970

MediumGelatin silver print

Dimensionsimage: 7 3/4 in x 8 7/16 in; mat: 14 in x 11 in; paper: 8 in x 10 in

Credit LineGift of Richard A. Hanson

Object number2005:362

About the ArtistHenri Cartier-Bresson once stated on behalf of himself, Robert Capa, and Brassaï, “Whatever we have done, Kertész did first.” Cartier-Bresson’s assessment extends beyond the immediate contact André Kertész had with the concentrated community of artists that he joined in September of 1925 in Paris, for Kertész embodied an uncanny ability to create in advance what avant-garde movements of the period held as ideals. Pure and concise, Kertész’s images render emotionally-rooted everyday scenes and objects into striking geometric compositions. On Reading, a series of photographs taken by Kertész in Romania, France, and the United States that spans his photographic career of over fifty years, illustrates the consistency and skill with which Kertész has photographed in this style. In this collection, however, Kertész’s penchant for street photography figures more prominently. The carefully orchestrated images in the original book version of On Reading present views of humanity, architecture, and the absorptive power of reading as a universal pleasure. In one image, a cow gazes over the shoulder of a man reading on a bench. In another, a boy crouches in a pile of newspapers reading as he clutches a melting ice cream bar. Through these poetic, and at times humorous, studies, Kertesz brings the solitary activity of reading to a new level, rife with humanistic touches. Sturdily balanced between geometric composition and playful observation, it is easy to understand how these glimpses of everyday people and places would come to influence the work of Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson.

These images did not, however, dominate the body of Kertész’s work. His oeuvre includes a variety of images clearly, though not conspicuously, influenced by the surrealist and constructivist movements. Positioning his camera adjacent to curved mirrors like those found in carnival fun houses, he created a series of distorted nudes. Characteristic of his overall approach, these images subtly reflect classic studies of the human form as well as the more recent developments and ideas sustaining the avant-garde community.

Kertész, born in Budapest, Hungary, began taking photographs in 1912. Before long, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army, where he volunteered for the Polish and Russian fronts. Wounded in 1915, Kertész returned to Budapest before moving to Paris in 1925. After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Paris was a vital axis of the international avant-garde and became the destination for artists Ergy Landau, Francois Kollar, Emeric Feher, Brassaï, Isis Germaine Krull, and Robert Capa, to name a few. Kertész circulated among the avant-garde literary and artistic groups and embraced the subjects, sights, and community ensconced in the City of Light. As the vitality of the community in Paris responded to political volatility within Europe, and the allure of New York’s artistic community and commercial opportunity grew, Kertész accepted an offer from the Keystone photo agency in New York. He moved with his wife to New York in 1936 and struggled there to establish himself as an artist and commercial photographer. In Paris, Kertész was approached by publications that wished to use his work. In New York, he was expected to conform to the artistic ideas of his editors or managers. His commercial engagements were often fraught with resentment because of the control imposed by his employers, and eventually, he abandoned the contract with Keystone, and likewise his later contract with Condé Nast publications. Due to the death of his beloved wife and what he considered to be the long overdue revival of interest in his work, Kertész withdrew from the world and worked from within the confines of his apartment. The product of this period, a book titled From My Window, details his melancholy emotions and perpetual nostalgia, but most importantly, it signals the final pulse of a masterly photographer whose art influenced some of the most heralded photographers of the era.