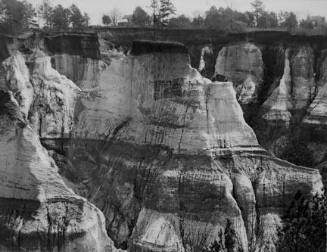

Erosion near Jackson, Mississippi

Maker

Evans, Walker

American, 1903-1975

DateMarch 1936

MediumGelatin silver print

Dimensionsoverall: 7 in x 9 in

Credit LineMuseum purchase

Object number2007:105

About the ArtistWalker Evans was a seminal figure in the development of American documentary photography in the early to mid-twentieth century. Born in St. Louis, MO, and raised in the Chicago suburb of Kenilworth, IL, Evans moved to New York City with his mother following his parents’ divorce. Evans studied literature at Williams College in Massachusetts and audited lectures at the Sorbonne in Paris before moving back to New York in 1927 to become a writer. The following year, he turned away from this ambition and began photographing the city, though Evans’s love of literature informed his work as a photographer. He cited photography as “the most literary of the graphic arts,” and throughout his career, he collaborated with writers. His early photographs of the Brooklyn Bridge (1929)—several prints of which are in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Photography—were published with Hart Crane’s long poem “The Bridge.” In 1930, Evans documented Victorian houses in the Boston area at the urging and funding of his friend, Lincoln Kirstein, and the resulting photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1933. Evans developed his photographic style early in his career. He worked in opposition to two famous photographers of the time, Edward Steichen and Alfred Steiglitz, stating, “I thought Steichen was too commercial and Steiglitz too arty, playing around, photographing the beautiful, calling it ‘God’…” In contrast, Evans produced highly detailed, frontal portraits and straightforward depictions of American life, aspiring to create photographs that were “literate, authoritative, and transcendent.” Evans believed that truth in photography was discovered, not constructed, and he relied on photography’s ability to precisely capture the stark and literal description of facts in sharp focus. He had a penchant for finding the extraordinary within the ordinary simply through observation, cultivating a documentary style and American sensibility that continues to influence new generations of photographers.

Late 1935 began a prodigious eighteen-month period for Evans, during which time he worked for the photographic unit of the Resettlement Administration (later renamed the Farm Security Administration, or FSA), a federal agency whose goal was to document and improve the plight of the rural poor during the Great Depression. Evans was often at odds with Roy Stryker, the director of the Resettlement Administration’s Historical Section, which housed the photography unit, and when faced with budget cuts in 1937, Stryker fired Evans. However, Evans had produced many of the images exhibited in American Photographs (1938), the first solo show given to a photographer by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Evans also collaborated with writer James Agee in the summer of 1936 on a magazine article about southern sharecroppers to create, in Agee’s words, a "photographic and verbal record of the daily living and environment of an average white family of tenant farmers." The article was never published, but the project grew into the groundbreaking book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), in which Evans’s photographs were published as a portfolio alongside Agee’s partly journalistic and partly poetic text.

Evans briefly worked for TIME magazine as a writer (1943-1945), and, for much of his career, for Fortune magazine as a writer and photographer (1945-1965). He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1940 and became a professor at Yale University in 1965. In 1968, Evans received an honorary degree from Williams College. Evans retired from Yale in 1971 but continued to be involved with its newly established photography graduate program as a visiting artist. His work is held in many collections and has been the subject of many retrospectives at such institutions at the George Eastman House, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and, notably, the Museum of Modern Art in New York in a 1971 exhibition simply entitled Walker Evans.

Lange, Dorothea

February 1936 [LOC, MoCP]

Lange, Dorothea

November 1936 [LC]

Lange, Dorothea

November 1936 [LOC]

Evans, Walker

October 1928, printed posthumously