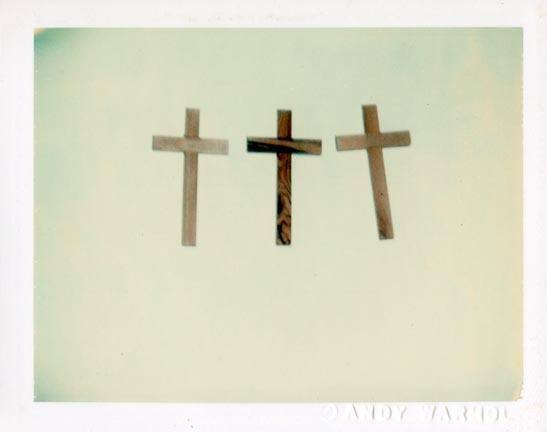

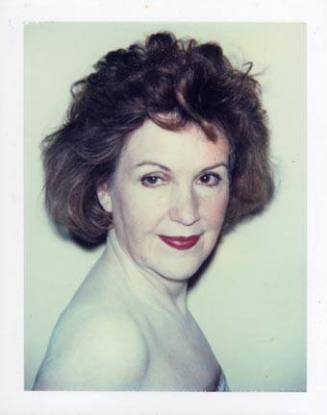

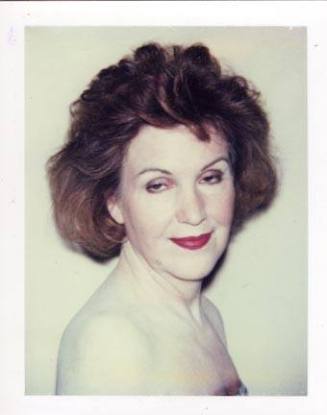

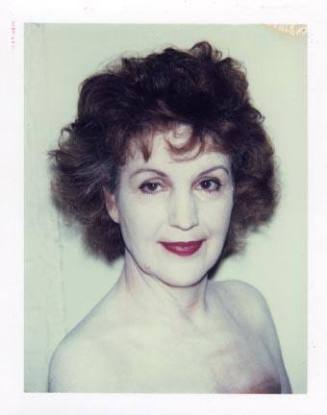

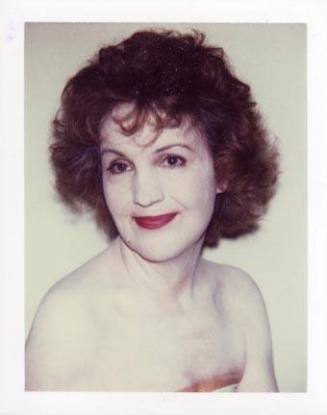

Crosses

Maker

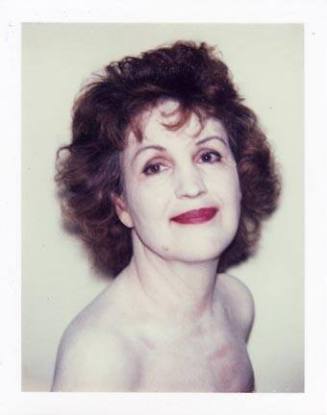

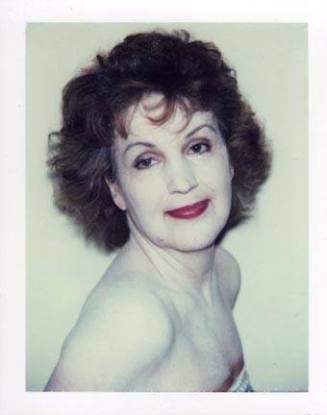

Warhol, Andy

American, 1928-1987

Date1982

MediumInternal dye diffusion transfer print

Dimensionsimage: 2 ¾ in x 3 ¾ in; paper: 4 1/4 in x 3 3/8 in; mat: 5 ¾ in x 6 ¾ in; frame: 7 ¼ in x 8 ¼ in

Credit LineGift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Object number2008:119

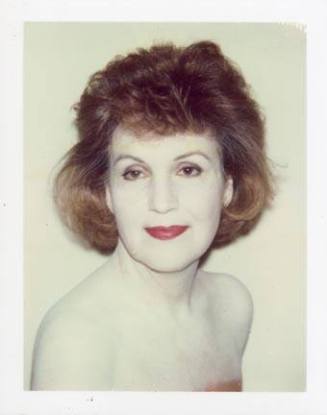

About the ArtistOne of the pioneers of Pop Art, Andy Warhol is known for destabilizing the division between consumer culture and fine art and for undermining conventional notions of originality. Iconic works such as his silkscreen reproductions of Campbell's soup cans and sculptural replicas of retail packaging—most notably Brillo boxes—adopt the mass-produced forms of consumer products in a deadpan manner. In other works, such as silkscreen paintings of legends like Marilyn Monroe, Warhol tapped into the growing cult of celebrity. Ultimately, Warhol's expansive practice encompassed numerous artistic media and merged the roles of artist, impresario, and businessman, as the head of a studio he dubbed The Factory. Warhol's photographs were rarely exhibited during his lifetime, but the medium played a central role in his practice from early on. Throughout his career, he made photographs in different formats and used photographic images as the basis for other works. More generally, he drew inspiration from the mechanical qualities of the camera and the photograph's inherent flatness. The 156 photographs by Warhol in the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s collection include examples of Polaroid portraits and black-and-white 35mm snapshots. These groups of images offer insight into the artist's working process and reveal his attachment to the camera as a means to create a visual diary.

In the early 1960s, Warhol used the photomechanical silkscreen process to reproduce publicity stills of celebrities or clippings from newspapers and magazines. Towards the end of the decade, he grew concerned about copyright lawsuits, and began making his own photographic material. Around 1970, Warhol was introduced to the Polaroid Big Shot, an instant film camera that he used thereafter as the starting point for a steady business of silkscreen commissions. With a fixed focal length and a built-in flash, the Big Shot was designed for portraits, framing a sitter's head and shoulders. Warhol's portrait sessions were systematic and repetitive, yielding a large reserve of raw material—up to 200 images per sitting—from which Warhol and his subject would select the best image for the silkscreen. He aimed to create an aura of glamour and often had his female sitters wear white make-up to cover any imperfections, a technique that yielded photographs that translated well as flattened silkscreen images. In addition to portraits, the museum holds a number of Polaroids by Warhol of male nudes and miscellaneous objects.

In 1976, Warhol was introduced to the Minox 35 El, a small 35mm camera, which he began to carry with him constantly. Recording his social activities, friends, and environment became a lasting obsession. For Warhol, these photographs were not utilitarian material for art, like his Polaroids were. Instead, the snapshots comprise a visual record of his life during the 1970s, illuminating the ranks of the rich and famous and publicizing his inclusion among them. Warhol once claimed, "a good picture is one that's in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous." He was largely indifferent to technique, and his black-and-white snapshots are deliberately amateurish and sometimes banal; it is not the image itself that sparks interest but the celebrity it depicts. Selections of the images were published in three books during Warhol's lifetime and printed in Interview, the magazine he co-founded in 1969.

These photographs were donated to MoCP by the Andy Warhol Photographic Legacy Program, which was founded by the Warhol Foundation in 2007 to increase public access to Warhol's photographs. To date, over 28,000 photographs have been distributed to university and college museums throughout the United States.