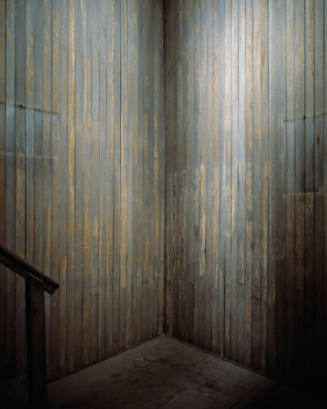

Field Museum -- FM 07-01-12 04

Maker

Van Rees, Jan Theun

Dutch, b. 1960

Date2007

MediumInkjet print

Dimensionsoverall: 40 in x 80 in

Credit LineExtended loan from U.S. Equities Realty

Object numberEL2008:22

About the ArtistArchitectural photographers generally make buildings look like they don’t. We correct perspective, eliminate background distractions, and wait for that perfect 15 minutes of daylight that makes the façade look like the architect’s drawing. And, of course, we do what photography is best at—we record surfaces. Jan Theun van Rees has broken through these conventions and gone beneath the visible skin of buildings in Chicago. In a sense, he has made the buildings transparent, allowing us access to the seemingly chaotic and asymmetrical service spaces and structural components that support the elegantly even exteriors.Another thing Van Rees has allowed us is a feeling of privilege—of following him into secret spaces after hard won access. We are being allowed into the minds of the architects and engineers, worlds of technical vocabulary and design principles that we can only pretend to understand.

On the photographic side of the project, some of the best thinkers and practitioners in the field began their careers making images of buildings. Beaumont Newhall, Edward Steichen, and John Szarkowski, the first three curators of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, fit this mold. One of Newhall’s earliest publications dealt with the subtleties of architectural photography. Walker Evans initially photographed bridges and buildings; Imogen Cunningham and Margaret Bourke-White spent time photographing industrial structures; Berenice Abbott worked as a professional architectural photographer in New York for part of her career. There are many more examples.

It is tempting to speculate that these luminaries were aware of and struggling with the superficial nature of photographic seeing and consequently spent the rest of their lives diving through the image surface to try to create meaning—to turn superficiality into a strength with metaphoric possibilities. Evans, for one, utilized shadows, reflections, and transparencies to qualify the autocracy of the surface of the photograph, and, by extension and example, the surfaces recorded by the photograph.

Photography is, at first glance at least, the greatest ally of Logical Positivism, the philosophy that holds that what you see is what is—that the meaning of the world around us is its surface with no mysterious hidden underpinnings. As much as Edward Weston championed the Creative Evolution philosophy of Henri Bergson, and his notion of the élan vital—“the living spirit behind the visible world”—what he managed to accomplish were beautiful renditions of the visible surfaces of bodies, peppers, sand dunes, etc. But Van Rees’s image of Holy Family Church above the alter (reminiscent of Frederick Evans’s 1896 image of the attic of Kelmscott Manor in Britain) might support Bergson. The photograph offers abundant visual metaphoric possibilities for the elaborate supporting structure behind religious faith. Perhaps this thinking could be extended to the images of the heating system in the basement of Unity Temple in Oak Park. Van Rees’s experiments give us something concrete on which to hang a suspicion that a city is not only its outward appearance. A city is what holds those structures up, what gives them their daily impact and long-term authority. It is the people that designed and built them and the people that work and live inside them. The surface is the equivalent of the shining traditions of civic pride and self-definition. Behind them—the secret spaces that Van Rees recorded—are chaotic and often mysterious ambiguities, secrets and confusions that nonetheless support the surface.

In “The Skyscraper,” Chicago Poems (1912), Poet Carl Sandburg notes “How hour by hour the sun and the rain, the air and the rust, and the press of time running into centuries, play on the building inside and out and use it.” Sandburg would have loved the philosophical and poetic strength of these photographs.

van Houtryve, Tomas

2007