Nickel, Richard

By the mid-twentieth century, urban regeneration and development in the United States spurred the demolition of treasured buildings. Facing this impending loss, historian and photographer Richard Nickel made his mark by campaigning for the preservation of American architecture. Since the 1950s, he lobbied for the protection of historic structures, researched and recorded their designs, and even personally salvaged some of their ornamental remains. Safeguarding the visual memory of these buildings, his photographs constitute another mode of preservation. His images’ emphasis on the physical might, efficiency, and utter beauty of architectural forms touts their viability and cultural significance.

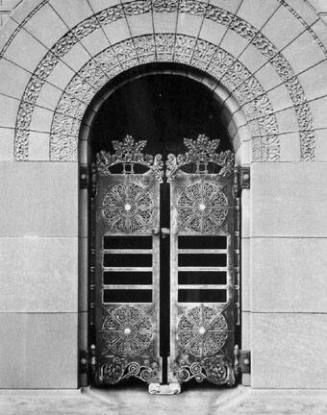

Nickel’s photographs championed the architecture of masters such as Burnham & Root, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright, who transformed the American landscape by merging new technologies with modern aesthetics at the turn of the twentieth century. Among this period’s innovators, Louis Sullivan emerged as a father figure whose buildings became Nickel’s primary pursuit. With the help of his former teacher, Aaron Siskind, Nickel sought to create a photographic catalogue of all the works by the firm Adler & Sullivan, a mission he literally died trying to complete. On April 13, 1972, the Sullivan Chicago Stock Exchange building unexpectedly crumbled, killing Nickel, who was inside documenting it.

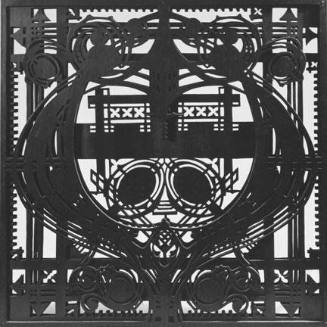

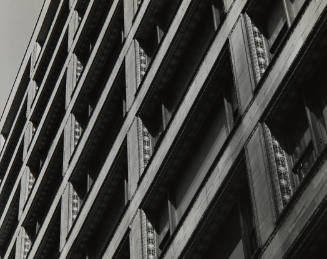

Nickel downplayed any personal insights or hints of expressiveness in his images proclaiming: “I prefer to be completely left out as the maker or interpreter.” Yet, as much as his orderly, black-and-white pictures give the impression of objectivity, by elaborating on the social and aesthetic vision behind historic buildings’ design, Nickel’s images portray his admiration for his architectural subjects. The image, Carson Pirie Scott and Co. (1955), illustrates how the Sullivan Center, formerly known as the Carson Pirie Scott and Company Building, facilitates the lives of Chicagoans. Nickel includes a suited man casually leaning on a signpost before the facade, which, in contrast to the man’s tilted body, appears especially upright and supportive. Nickel also showcases the commercial features of the building with a horizontal composition that underscores the wide window displays. The man’s small size in relation to the backdrop suggests the building’s monumental portions, but Nickel’s close frame allows us to see how Sullivan’s ornamental details subtly enhance the streets.

When depicting buildings from a greater distance, Nickel presented the structures as integral to their environments. Auditorium Building, Chicago captures what was once Chicago’s tallest skyscraper. Nickel depicts the Auditorium soaring above the city by shooting it from a neighboring rooftop and incorporating an overhead view of the street below. Posing the Auditorium as part of the city’s fabric, Nickel includes a glimpse of its ground level arcades, evoking the crowds that passed through the space when it was an office, hotel, and opera house complex. To the extent that Nickel’s photographs celebrate the merger of stylistic and structural advances in architecture, his work pays homage to Sullivan’s philosophy of “form follows function.”

Richard Nickel was born in 1928 in Chicago. He studied under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind at the Institute of Design (later part of the Illinois Institute of Technology) in Chicago, where he completed a BA (1954) and an MFA (1957). Aaron Siskind, John Vinici, and Ward Miller finished Nickel’s photographic compilation, The Complete Architecture of Alder & Sullivan (2010). Nickel is also the subject of the books, Richard Nickel Chicago: Photographs of a Lost City (2008) and They All Fall Down: Richard Nickel's Struggle to Save America's Architecture (1994). His work belongs to the collections of Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Polish Museum of America in Chicago, and the Society of Architecture Historians, among others.