Weston, Brett

In much of his work, Brett Weston transforms elements of the natural or urban landscape into abstract forms, emphasizing formal qualities such as light and shadow, pattern and shape. To do so, he often used a close-up viewpoint and meticulously framed compositions, while anticipating the additional degree of abstraction that results from converting a fully-colored world into a black-and-white image. Weston’s untitled photographs of scrub grass on the face of a sand dune (1946, 1947) aptly demonstrate these tactics and tendencies. The framing of the images isolates the plants from their larger context and flattens out a sense of depth, leading them to appear as dark shapes hovering above a lighter background.

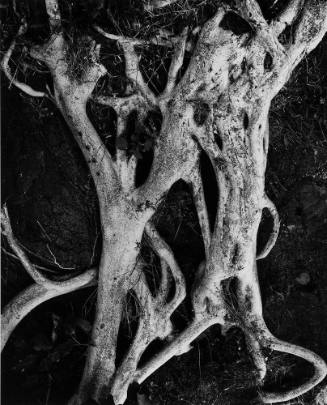

Brett regularly photographed certain subjects, most notably abstracted botanical details such as leaves, kelp, tree roots, or reeds in still water. Nevertheless, his work underwent certain stylistic changes over the course of his career. One can observe, for example, different formal priorities in his photographs of White Sands National Park in the 1940s, which have a wide tonal range, and his photographs of junked cars in the late 1970s, which have more extreme contrasts of black and white that push the images closer towards a state of pure formal abstraction.

Of Edward Weston's four sons, Brett seemed most assured, from an early age, to have a career in photography. At thirteen, Brett went with his father to Mexico, where he became his father's apprentice and mixed with artists such as Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Tina Modotti. Before he was twenty, Brett had achieved international recognition, owing primarily to the inclusion of his photographs in the pivotal avant-garde exhibition Film und Foto in Stuttgart, Germany in 1929. There, his work was seen alongside photographs by Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, and Paul Outerbridge, among other notable figures. In 1932, at the age of twenty-one, Brett had his first solo show at the M. H. de Young Museum in San Francisco. Subsequently, he was stationed in New York for the army, and later owned a studio and portrait business in Los Angeles. He also traveled for periods of time to photograph in places such as Alaska and Japan. In the late 1940s, Brett returned to Carmel, California to attend to his ailing father and to concentrate on his own creative work. He resided there primarily until the late 1970s, when he began living and working in Hawaii. He died in Kona, Hawaii in 1993.