Yokomizo, Shizuka

Shizuka Yokomizo uses photography and video to examine the relationship between the self and the other. Looking beyond the strictly representational possibilities of the photographic image to what remains unseen, her work draws on the potential of these media to convey the often-intangible contours of an encounter between photographer and subject, to suggest multiple vectors of awareness, and to uncover a dialogue between public and private realms. Her series Stranger (1998–2000) centers on a momentary confrontation between observer and observed. At its core it is a collaboration of sorts: Yokomizo sends her subjects an anonymous letter proposing they stand in the front window of their home at a specified date and time, at which point the artist arrives outside, sets up her tripod and camera, exposes her film, and then leaves. The subjects are instructed to turn on all their lights, wear their usual clothing, and remain still—or if they choose not to participate, to signal this by drawing their curtains. Because the hour selected is during the night, Yokomizo's subjects can discern the photographer only as a dark silhouette.

Photography, with its special capacity for identification, observation, and implication, allows unprecedented access to and evidence of otherwise private and restricted moments. In this case, the barriers Yokomizo often includes in the foreground of her pictures—window moldings, curtains, and security gates—clearly articulate layers of distance and enhance the feeling of voyeurism. But if the camera long ago proved to be the perfect tool for the pleasure of witnessing someone caught off guard, the success of Yokomizo's Stranger series, in contrast, depends on the willingness of her subjects to place extraordinary trust in a stranger. The photographs are intimate in their complicity. Asked to perform, her subjects acquiesce, while their body language ranges from suspicious to hostile to amused to nervous. Yokomizo, for her part, could have taken her photographs from a concealed location or simply pointed her camera through the window when the person inside least expected it, but she purposefully enters the realm of her subjects and allows herself to be seen, if only as a shadowy figure. In a sense she is performing for them as they are performing for her: while making a photograph she is also acting out the role of the anonymous, voyeuristic photographer—a familiar but persistently disconcerting trope that Yokomizo brings to life for her subjects in the comfort of their own homes. To look at one of Yokomizo's pictures is to adopt her vantage point, staring in through the window, but Yokomizo's pictures make it difficult to slip into the detached position of viewer-as-voyeur since they unremittingly imply the photographer's presence, wedged between the viewer and the posing stranger. Even though they depict a solitary person, her photographs in this way are less conventional portraits than highly charged records of an encounter.

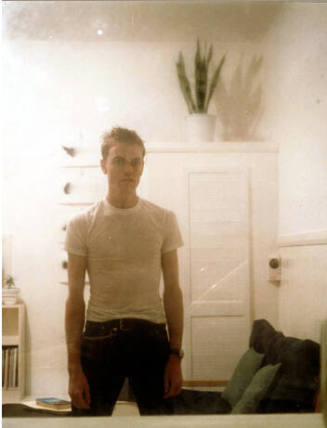

Yokomizo's Stranger series reveals a shadowy, indistinct boundary between public and private. Qualities that usually seem at odds become thoroughly entangled: distance and intimacy, anonymity and exposure, collaboration and control, surveillance and exhibitionism. Perhaps just as importantly, each of the photographs in the series registers the tension of the encounter and the fragility of its terms, which might change at any moment. Yokomizo speaks of being nervous before going to photograph a stranger, but rarely in her work is her own vulnerability underscored to the degree it is in Stranger (5). In this photograph the window frame, visible in most of her pictures, is notably absent and a young man stares out defiantly, even aggressively. Without the clear demarcation between inside and outside the gulf between photographer and subject seems less stable and the implications of the encounter less certain.