Althouse, Stephen

American, b. 1948

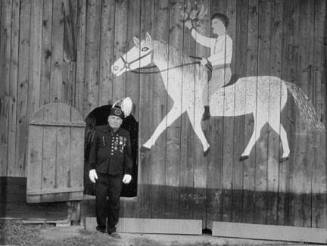

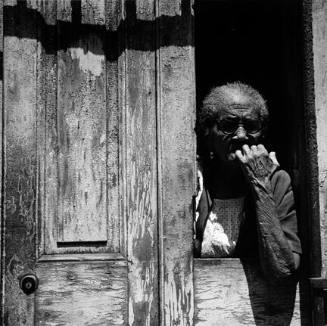

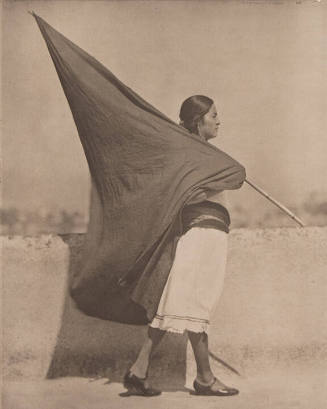

In the 1930s, Alvarez Bravo started to pursue a new direction in his work, focusing on urban street life while exploring the theatrical aspects of ordinary activities. His compositions continued to evince a modernist interest in form, but he imbued his photographs with symbolism, a sense of fantasy, and allusions to Mexican tradition. Characterized by enigmatic visual juxtapositions, many of his photographic vignettes have the qualities of a parable or fable. In Parabola Optica [Optical Parable] (1931), for example, Alvarez Bravo uses the camera to transform an ordinary storefront into a parable about modern vision by tightly framing the painted eyes on the shop's windows so they appear to look out in all directions, beneath a sign that states "la optica moderna," printed in reverse. Alvarez Bravo was opposed to leaving works untitled, and he routinely titled his works with cryptic phrases that suggest hidden meanings.

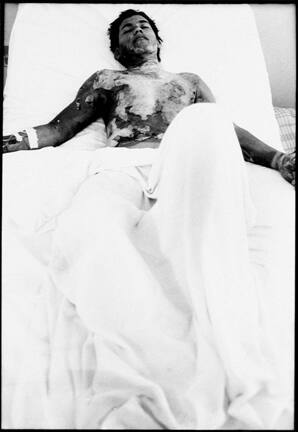

In 1932 Alvarez Bravo worked briefly as a cameraman for Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein on his production ¡Que Viva Mexico! The project was never finished, but Alvarez Bravo went on to pursue an interest in cinema and try his own hand at filmmaking. He worked for some time in the Mexican film industry. It was as a photographer, however, that he gradually earned international renown. In 1935, Alvarez Bravo participated in an exhibition at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York along with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans. Three years later, in 1938, Surrealist Andre Breton met Alvarez Bravo while traveling in Mexico, and he came to embrace the photographer as "a natural surrealist." The following year, Breton invited Alvarez Bravo to provide the cover image for an exhibition catalogue of Surrealist art, for which he created La Buena Fama Durmiendo [Good Reputation Sleeping], a mysterious but serene photograph of a nude woman wrapped in bandages, lying beside a cluster of cactus spines. In the 1940s and 1950s, interest in Alvarez Bravo's work continued to grow, as evidenced by his place in such major exhibitions as Edward Steichen's The Family of Man, but he remained relatively unknown in the United States until the 1960s.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo continued making photographs that centered on everyday life in Mexico, but he did not limit himself to a certain style or subject. In the 1940s, he began photographing the Mexican landscape, and in his later years, he worked primarily in his studio, photographing nudes. In 1997, five years before his death, The Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a retrospective of his work. His photographs remain touchstones of modern photography, but Alvarez Bravo also had a direct impact as a teacher and friend on a number of photographers, including Graciela Iturbide, Eniac Martinez, Ruben Ortiz, Yolanda Andrade, and Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, who have achieved great recognition in their own right.